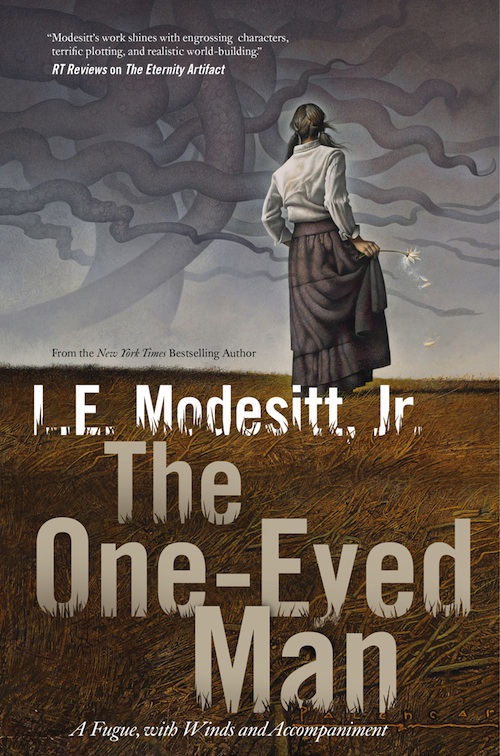

Check out L. E. Modesitt, Jr.’s new novel, The One-Eyed Man, out on September 17:

The colony world of Stittara is no ordinary planet. For the interstellar Unity of the Ceylesian Arm, Stittara is the primary source of anagathics: drugs that have more than doubled the human life span. But the ecological balance that makes anagathics possible on Stittara is fragile, and the Unity government has a vital interest in making sure the flow of longevity drugs remains uninterrupted, even if it means uprooting the human settlements.

Offered the job of assessing the ecological impact of the human presence on Stittara, freelance consultant Dr. Paulo Verano jumps at the chance to escape the ruin of his personal life. He gets far more than he bargained for: Stittara’s atmosphere is populated with skytubes—gigantic, mysterious airborne organisms that drift like clouds above the surface of the planet. Their exact nature has eluded humanity for centuries, but Verano believes his conclusions about Stittara may hinge on understanding the skytubes’ role in the planet’s ecology—if he survives the hurricane winds, distrustful settlers, and secret agendas that impede his investigation at every turn.

1

Court procedures on Bachman were old-fashioned, requiring all parties be present. So there I was, after two hours of evidence and testimony, on one side of the courtroom, standing beside my advocate, Jared Hainsun, before the judge’s bench, and on the other side was Chelesina, with her advocate. Chelesina didn’t look in my direction. That didn’t surprise me. For the three years before she left, she’d barely looked at me even when she’d been looking at me. That didn’t bother me so much as the way she’d set me up after she’d split . . . so that the only option was no fault.

The judge looked at me. I could have sworn that the quick glance she gave me was almost pitying. I didn’t need that. Then she cleared her throat and spoke. “In the proceeding for dissolution of permanent civil union between the party of the first part, Chelesina Fhavour, and the party of the second part, Paulo Verano, the Court of Civil Matters, of the Unity of the Ceylesian Arm, located in the city of Smithsen, world of Bachman, does hereby decree that said civil union is hereby dissolved.”

She barely paused before going on. “In the matter of property allocation, the net worth of the assets of both parties has been assessed at five point eight million duhlars. The settlement to the party of the first part, Chelesina Fhavour, is four point one million duhlars, of which three million has been placed in an irrevocable trust for the daughter of the union, Leysa Fhavour, said trust to be administered by the Bank of Smithsen until Leysa Fhavour reaches legal civil and political maturity . . .”

At least, Chelesina can’t easily get her hands on that.

“. . . Civil penalties for breach of union are one point five million duhlars, to be split between you, as mandated under the laws of the Unity. The remainder of all assets is allocated to the party of the second part, Paulo Verano.

“The court will revisit the situation of both partners in one year and reserves the right to make further adjustments in asset placement. That is all.”

All?

I looked at Jared.

He shook his head and murmured, “They let you keep the conapt.”

And two hundred thousand duhlars. “But . . . she left me.”

“No fault,” he reminded me.

Three million for Leysa, when she hadn’t spoken to me in two years. When she had only a year left at the university? When her boyfriend’s father was the one for whom Chelesina had left me?

So . . . out of some six million duhlars, I had two hundred thousand left . . . and a small conapt in Mychela. And a consulting business that the Civil Court could suck duhlars from for another two or possibly three years? All because I went to bed with someone besides Chelesina a year after she’d left me?

Jared must have been reading my mind . . . or face, because as we turned to leave the courtroom, he said quietly, “Equal no fault doesn’t weigh things.”

“I know that. I do have a problem with most of my assets going to an ungrateful daughter who won’t speak to me even after I’ve paid all the bills for years.”

“That’s Unity policy. Permanent civil unions are supposed to protect the children. If the civil union is dissolved, the Court allocates enough assets to ensure that the child or children are adequately protected and able to continue in roughly the same lifestyle as before the dissolution.”

“Which punishes me for making sure she was educated and raised with all advantages,” I pointed out. “It doesn’t punish Chelesina.”

“It can’t. Her design firm went bankrupt.”

I had my doubts about the honesty of that bankruptcy, but Jared would just have told me what I already knew.

There wasn’t a thing I could do about it.

2

Spring was the garden of my sky, thought one,

Where there we loved in joy and saw no sun.

“Daisies are the perkiest flowers, don’t you think?” Ilsabet looked to the wall and to Alsabet, framed in the wallscreen. “Petals of sun and light, centers of ink.”

“If they don’t get caught in the wind,” replied Alsabet. “Then they’re just scattered petals.”

“The skytubes let them be, as any can see.”

Alsabet was silent, as if waiting for a prompt.

“I know,” Ilsabet finally declared, “because it’s so.”

“How do you know?”

“I just do. But I won’t tell you. You’d tell them now, but you don’t know how.” With that, Ilsabet’s hand came down in a cutting motion, and the wallscreen blanked. After a moment she smiled. “I know you’re still there, but it makes me feel things are fair.” Her voice changed slightly. “I’m going outside. Matron says I can go and bide. I wish there were a storm today, but they’ve all gone away. So the door will open for me. It only closes when I want to see. I learned to know that about doors a long time ago.”

Her grayed braids swung girlishly behind her as she danced out through the door that had irised open at her approach. Once outside, her wide gray eyes lifted to behold the twisted purple tubes that festooned the sky to the south. Far to the south. Too far.

3

For the next few days, I didn’t do much of anything, except wind up the handful of contracts I had and step up my exercise. Over the past few months, I hadn’t been as assiduous as I should have been in looking for new clients, but it’s hard to think about ecology, especially unified ecology, when you’ll have to subcontract “experts” in order to provide the expected range of credentials and then pay their fees. Especially when you’re worried about getting fleeced and when you suspect anything left after your expenses will go to your former spouse. I hadn’t even considered that so much would go to Leysa. Needless to say, she’d never contacted me, either by comm or link . . . or even by an old-fashioned written note.

The netlink chimed. . . and I frowned. I thought I’d turned off the sonics. Still . . .

After a moment I called out, “Display.” The system showed the message. Simple enough. It just said, “After everything, you might look into this.” The name at the bottom was that of Jared.

What he suggested I look into was a consulting contract proposal offered by the Unity’s Systems Survey Service. I read the proposal twice. It looked like the standard wide-spectrum ecologic overview contract, but there were two aspects that were anything but standard. One was the specification that the survey had to be done by a principal, or a principal and direct employees—no subcontracting essentially. The second odd aspect was that the contract amount ranges were staggering for a survey contract. Together, that meant the survey had to be not only off-planet, but most likely out-system, very out-system.

Out-system meant elapsed relative travel-time . . . and that might not be all bad.

I thought about dithering, but I didn’t. Instead, I sent a reply with credentials and vita.

I had a response in less than a standard hour, offering an appointment in person later in the day, or one on twoday of the next week or threeday of the following week. The in-person requirement for an initial interview was definitely unusual. Since I wasn’t doing anything but stewing in my own juices, and since the interview was in the Smithsen Unity Centre, less than half a stan away by tube, I opted for the afternoon interview. Then, I had to hurry to get cleaned up and on my way.

I actually arrived at the Unity Centre with enough time to spare, and was promptly handed a directional wand to lead me to my destination— and told that any significant deviation could result in my being stunned and removed from the Centre. I followed the wand dutifully and found myself in a small windowless anteroom with three vacant chairs and an empty console. Before I could sit down, the door to the right of the console opened, and an angular figure in the green and gray of the Ministry of Environment stood there. Since he wore a belt stunner, I doubted he was going to be the one interviewing me. At least, I hoped not.

“Dr. Verano?”

“The same.”

“If you’d come this way, please.”

The Ministry guard guided me down a corridor to a corner office, one with windows and a small desk, behind which sat a man wearing a dark gray jacket and a formal pleated shirt, rather than the gray-blue singlesuits of the Systems Survey Service, indicating he was either a classified specialist or a political appointee. That, and the facts that there was no console in the office and that a small gray-domed link-blocker sat on the polished surface of the desk, suggested the proposal to which I’d responded was anything but ordinary. He gestured to the pair of chairs in front of the desk and offered an honest warm smile, but all good politicians or covert types master that early on or they don’t remain in their positions, one way or the other.

“We were very pleased that you showed an interest in the Survey proposal, Dr. Verano. Your credentials are just what we’re looking for, and you have a spotless professional reputation, and the doctorate with honors from Reagan is . . . most useful.”

I wondered about the inclusion of the word “professional.” Was he one of the Deniers, the right wingers of the Values Party? Or was he just being careful, because the second speaker was a Denier, and the SoMod majority was nano-thin? “I’m glad that you found them so. I am curious, though. Why were you so quick to reply?” I had to ask. Most proposals from the Unity government took months before they were resolved even, I suspected, “unusual” ones.

“Ah . . . yes. That. There’s a matter . . . of timing.”

“Out-system transport timing?”

“Precisely. The system in question has but one scheduled direct leyliner a year, and it departs in three weeks.”

And sending a special ship would raise questions—and costs—that no one wishes to entertain. “Can you tell me more about the survey I’m to conduct?”

“It’s a follow-up to gather information to determine whether the ecological situation on the planet requires continuation of the Systems Survey Service presence, or whether that presence should be expanded or reduced . . . or possibly eliminated.”

“Given that we’re talking one ley-liner a year, this has to be a system at the end of the Arm. That’s a lot of real travel-time.”

“And you wonder why we even bother?” The man who had not introduced himself, and likely would not, laughed. “Because the planet is Stittara.”

That, unfortunately, made sense.

“I see you understand.”

“Not completely.” I did understand that the Unity Arm government didn’t want to abandon Stittara, not given the anagathics that had been developed from Stittaran sources, and what they had done in boosting resistance to the Redflux. On the other hand, the costs of maintaining outposts were high—and there had always been the question of whether and to what degree the indigenous skytubes might be intelligent, or even sentient. The Deniers, the anything but loyal opposition, and several minority parties questioned the need for far-flung outposts, while the Purity Party wanted all connections to “alien” systems severed, notwithstanding the fact that almost all systems were alien to some degree. “Funding, skytubes, anagathic multis threatening the uniqueness of Stittara, the threat of takeover from the Cloud Combine?”

“Any of those could certainly be issues, but the contract only requires delivery of an updated ecological overview of conditions on Stittara.”

I managed not to laugh. Whatever report I made wouldn’t even reach the government for over 150 years. What the unnamed functionary was telling me was that the Unity Arm government was under pressure and that they had to come up with a series of concrete actions to defuse the larger issue raised by the opposition parties.

“We had thought you might find the contract fit in with your personal goals,” he added.

Had Jared told someone what had happened? It wasn’t out of the range of possibilities, given that his aunt was a well-placed senior SoMod delegate. I was getting the definite feeling that the SoMod majority in the assembly had barely held in the face of systems-wide concern that private entities might either be destroying something unique on Stittara or, conversely, because of Denier concerns that the government was wasting trillions of duhlars in research subsidies and tax credits on research that either benefited the wealthy or was pointless. The contract certainly wouldn’t be described that way, and there likely wouldn’t be much media attention, but if I accepted the contract, I would become a small bit of SoMod political insurance, among other steps of which I knew little, only that they had to exist, to allow the first speaker to claim, if and when necessary, that steps had been taken. So I’d be highly paid, lose all contacts with my past life, and no one would even know how the problem might be resolved, or if it would be, but the first speaker could claim it had been addressed, at least to the best of anyone’s ability.

“It might,” I admitted.

After that, it was merely a matter of negotiation, and not much at that, because I knew they could make my life even more difficult than it was, and also, that taking the contract would mean Chelesina couldn’t do much more to me. In fact, the relativistic time dilation of some seventythree years one-way was looking better and better. With any luck, Chelesina would have doddered into seniority and forgotten me, or at least found some other ram to fleece, by the time I returned to anywhere in the Arm. Why the Unity accepted my proposal so quickly I had no idea, except there probably wasn’t anyone else with my experience in ecological interactions who was desperate or crazy enough to want the assignment . . . and they wanted political cover quickly.

The up-front bonus, while not huge, combined with what I’d get from the sale of the conapt and the few hundred thousand I had left, would create enough to purchase a dilation annuity, hopefully compounded substantially. That might actually amount to something when I returned, and I’d still be physically young enough to enjoy and appreciate it. If everything went to hell, and that was always a possibility, at least I’d be away from the worst of the collapse.

And who knew, the Stittara assignment might actually be interesting.

4

I made it away from Smithsen before my contract became public . . . but not away from Bachman. Well, not out of orbit. The Persephonya was about to break orbit when I got a message from Jared, with a linknet clip of a sweet-faced woman talking about the last-moment efforts of the SoMods to influence the elections with a series of expensive cosmetic and very political actions. Mine wasn’t the first listed, but it was far from the last, and the bottom line was that the SoMods were spending millions if not billions of duhlars on useless surveys and assessments whose results wouldn’t be seen for decades, if not generations . . . if at all. And, of course, they had to provide a return bond as well, in the event that something catastrophic had occurred on Stittara, either physically or politically. I didn’t worry about the physical catastrophes. Planets were pretty stable as a whole, and it took hundreds of millions of years to see any basic changes. Political changes were another matter, but, again, given Stittara’s low population, the reliance on Arm technology, even if filtered by time, and the distance from Bachman, it was unlikely I’d be declared persona non grata upon arrival. If that did happen, I’d still get return passage and my bonus . . . and that wasn’t bad.

The media summary on my assignment was simple: Stittara is the source of anagathics that have more than doubled the life spans of Arm citizens. Why spend millions to reassess what’s already known.

The Ministry of Environment view I’d been given earlier was somewhat different: Do an environmental assessment to make sure no one is altering the environment on Stittara, because the research of that environment has created and continues to create products that affect billions of lives . . . and supports billions of duhlars in research, investment, and healthcare products.

Jared also sent a confirmation that he’d filed the documentation and the taxes on the proportion of my contract advance that I was transferring with me to Stittara. I’d learned from some of the old-timers that no matter where you thought you were going to go, it wasn’t a good idea to go somewhere, especially somewhere multiples of light-years away, without enough assets to last a while—or to give you the chance of a new start. I hardly planned on that, but it’s always better to learn easily from others’ experience than the hard way by making the same mistakes yourself.

I sent back a query asking about anyone I should watch out for, and his response was, as usual, less helpful than it could have been.

“Not until you debark on Stittara.” That meant he didn’t know or wouldn’t say, neither of which was useful. Or that nothing would happen onboard the Persephonya, which I’d already figured out.

I sent him a simple “Thanks!”

I didn’t expect a reply, but there was always a chance. In the meantime, I left my links open and went to explore the ley-liner . . . or what of it was open to “standard” passengers, which equated to “second-class” passengers, all that the Survey Service was paying for. Personally, I could see that standard meant second-class, and that was what I had expected, and the way in which I regarded all of us in “standard accommodations.” At least, I didn’t have to go under life-suspension. That was true steerage, with the added risk of long-term complications, which was why the Survey Service could justify the cost of standard passage for a consultant.

Besides the cubicle termed a stateroom, there wasn’t much to explore—an exercise room, too small to be called a gym; the salon, with tables for snacks and talking and cards or other noninteractives; the dining room; and, lastly, the observation gallery, which I knew would be closed off once we entered translation space. At that moment, though, the gallery was where most of the passengers, all twenty-odd of those of us in second class, were located.

From there, through the wide armaglass ports, Bachman hung in the sky like a huge sapphire globe smudged with clouds, poised against the sparkling sweep of the Arm. I got there just in time to see the umbilical from the orbit station retract—Orbit Station Four, to be precise, the smallest of the five. Several of the men standing at the back of the gallery looked slightly green. Ultra-low grav will do that to some people.

At first, the Persephonya’s movement was scarcely perceptible.

By the time we were moving out-system, I sat down in the salon, by myself. Once the ship was away from a planet, the view of the stars and the Arm didn’t change, not to the naked eye, anyway.An attractive blackhaired woman in a tailored shipsuit that showed off her figure, just enough, settled into the chair and table beside mine. She had to be older, not that I or anyone else could tell by her appearance or her figure, but because her features were finely chiseled in the way that never happens with young women, and her dark eyes had seen at least some of life without shielding.

“You’ve seen the Arm from out-planet before, haven’t you?” she asked in a way that really wasn’t a question.

“A few times. I’m Paulo Verano, by the way.” That wasn’t giving a thing away.

“Aimee Vanslo. What business takes you to Stittara?”

“A consulting assignment. What about you?”

“Family business. I’m the one the others can do without for now.” She laughed humorlessly. “Besides, it’s the only way I’ll end up younger than my children, and I do want to see them after they’ve realized that they don’t know everything they think they do.”

“And you’re effectively single,” I replied, smiling politely, and adding, “and you don’t play on my side.”

Her second laugh was far more genuine. “You have seen more than the Arm. You obviously are widowed or dissolved.”

“Not single by choice?” I countered.

She shook her head. “You’re not a beauty boy, and you’re obviously intelligent, and the only ones who would pay for you to travel to Stittara are the Arm government or one of three multis. They wouldn’t send a permanent singleton. No loyalties.”

“Very perceptive. Do you want my analysis of you?”

“No. You may keep it to yourself. My partner was killed in a freak accident three years ago. The children are all grown, but young enough to think they know everything. My ties lie in the family business.” She shrugged. “I like intelligent conversation without complication. Unless I miss my guess, you’ll do nicely.”

I smiled. “So will you.”

“I know.”

We both laughed.

“What are you comfortable telling me about your business?” I asked.

“Only that it’s in biologics.”

“And it’s very big,” I suggested.

“It’s only a family business.”

She wasn’t going to say. “And your expertise?”

“Management and development. I’ll talk about theory and what I’ve observed anywhere outside the biologics field. And you?”

“Ecologic and environmental consulting, and I’ll talk about anything except my current assignment.”

“Which has to be on Unity business.”

“Anything but my current assignment.” If she could limit, so could I . . . and I should. She nodded. “What do you think about the fiscal posture of the Arm Assembly?”

“Mass-wise and energy deficient, so to speak.”

At that point a steward arrived. Aimee ordered a white-ice, or whatever the vintage was that the staff was providing as such, and I had an amber lager.

If she happened to be what she offered herself as, she was unlikely to be one of those who I needed to watch out for…but who was to say she was exactly what she said she was? And what sort of family business could afford to send someone as far as Stittara, unless it was truly huge? In which case, why was she traveling standard class?

I doubted I’d be getting any answers soon, but talking with her was likely to be interesting, and if I listened more than I talked, which was often hard for me, I might learn more than a few things I didn’t know.

The One-Eyed Man © L.E. Modesitt, Jr. 2013